Reflections on a Winter Retreat: Norfolk 2025

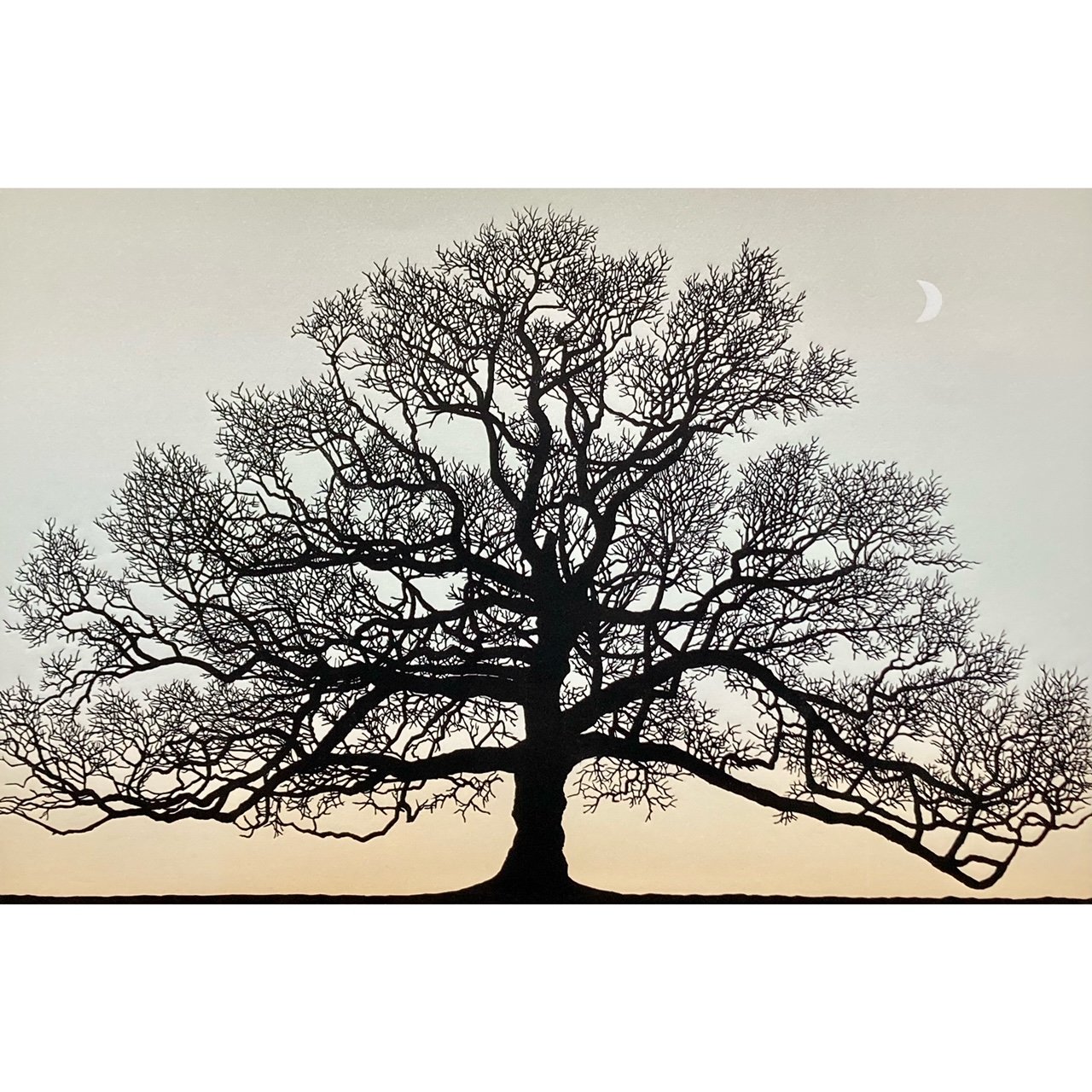

Trees in Winter.

Once, on a wintery walk in Canada, my father who taught me the value of walking in silence to learn how to pay attention to nature, and to be with one’s own thoughts, and feelings, broke the quiet of the woods by suddenly telling me something I hadn’t known about my mother.

The usual atmosphere of the Canadian woodland was muted by heavy snowfall the night before, and the silence of our walk was interrupted only by the sound of our winter boots crunching in the crisp bright white snow underfoot.

It was so unusual for my father to chat while we were walking and the path between the pine trees required us to walk in single file, so I wasn’t expecting conversation and paid attention immediately when he spoke. He said, simply, “your mother loved trees in winter.”

After a pause, in which I knew he was waiting for me to take in this information, he added simply, “have you noticed?” He gestured to a magnificent tree ahead, standing alone in a clearing. This tree, unlike the Canadian pines all around was remarkable because like most English trees in winter, it was bare of leaves, striking a silhouette against the blue sky of the morning. My father’s words revealed the tree to me in a new light; I realised I hadn’t ever really noticed or fully taken in how spectacular they are - the trees that are stripped of their leaves by the season. In England, I think we take this beauty for granted.

The gem of this remembrance of my mother struck me in the same way that an unexpected sharing of a secret might; something precious was exchanged between my father and I, but we didn’t elaborate and never spoke of it again. It was a moment in time that changed my perception of the world, and subtly, my sense of my father’s relationship with my mother.

The moment was brought instantly to mind again recently when I happened upon a beautiful hardback book at Christmas entitled Trees in Winter by Richard Shimell. The book tells the story of the author’s love of walking, how walking in and reflecting on nature has allowed him to navigate and survive the most difficult challenges of his life, and the book speaks of his love of trees, especially in winter.

I knew instantly that the book would provide fertile inspiration for my winter yoga retreat in the New Year in Norfolk. The book tells of the author’s radical change of career later in life, and his journey to becoming an artist by transforming his close attention to nature into art practice after learning how to make lino-cut prints. In the life story that intersects the binding of one beautiful print after another, Shimell tells of the healing power of the English landscape and the significance for his life of learning and practising a craft that requires the slow development of mastery over hand tools. He narrates the journey of perception in which making prints leads him to pay closer and finer attention to the rural environment, and especially ancient oak trees, the winter fields they stand in and the changing skies and winds they are transformed by.

Richard Shimell: Ancient Oak

By looking closely, and capturing what he sees, Shimell is himself changed by his craft into a different kind of person than he had been before. Once a journalist, he is now an artist among other contemporary artists and story tellers in England who are collaborating to produce a breathtaking body of work that is both an ode to the land – a glorification of the countryside - but also an urgent call for conservation at a time of cultural shift that means people are increasingly looking the other way as the environments we take for granted are threatened. The book tells of species loss due to changing farming practices and other environmental changes that signify even among those whose livelihood depends on the land, a tragic loss of appreciation for nature and a subsequent failure in families to teach children to learn how to see and to know the landscape, and the creatures and life forms that inhabit it.

The nature writer, Robert Macfarlane and artist Jackie Morris are part of this movement for the rediscovery and romanticisation of the rural landscape in England. Their beautiful collaboration in the Lost Words and Spell Songs project has produced the most stunning collection of paintings, and poetry to evoke and celebrate the animals and birds that form the unique character of the English countryside. Their rhapsody on nature has curated a meditation on English personhood: they ask of us what kinds of persons we are becoming if we do not know our land intimately, do not care about the fate of its species and do not immerse ourselves in it, as Shimell has done, as my father taught me to do, as a form of medicine for the heart and soul. I am reminded of and rest more often now in appreciation of a childhood spent bird watching with my father, in relative silence of course, coming to know the birds of England intimately by sight, song, nest and flight.

Jackie Morris: Hare and Goldfinch

Jackie Morris: Barn Owl

Barn Owl

Below, barn owl spreads silence -

All sound crouches to ground,

Runs for cover, battens down;

Noise is what owl hunts, drops on, stops dead.

Over rushes, across marshes, owl hushes –

Will you listen with owl ears for a while?

Let our world’s din deafen you,

Let owl’s world’s whispers call you in.

Snow Hare

Snow hare whitens as the year turns dark.

Night rises, rain falls as sleet on higher ground.

On moors, by tors, in peat, hare hunkers into form;

Weathers what would kill you without fight.

Hare, walking, is graceless lollop.

Awkward piston, awkward shunt.

Running, hare smooths sudden into speed,

Flows over hill-top, lee-slope –

Each quick arc a mark of hare, a sign of hope.

The Lost Words Robert Macfarlane and Jackie Morris (2020).

Unexpectedly, a few books came together in a beautiful collaboration among guests on winter retreat this year to form a shared contemplation not just of the value of winter for quietening into stillness, and restorative rest, but also the importance of attending to what remains wild as the means to come back into alignment with our own human nature.

Many guests had just read, or listened to on audiobook, another recently published autobiographical work – by Chloe Dalton - entitled Raising Hare. The book is a lovely meditation on a life usefully thrown into disarray by an unexpected encounter between the author and a baby hare (a leveret) abandoned by its mother for some unknown reason on a rural pathway. Chloe, a busy political advisor working in London, tells of her life in the countryside during Covid, she reveals the contrast between this and her former life in which she hardly stopped to come down to earth, because of frequent travel and a frantic work schedule that meant she was mostly away from home, often on the other side of the world, aware of how ungrounded and out of balance her life was, but unable to bring about change.

Brought to a sudden standstill by Covid isolation, Chloe takes a daily walk in her rural surroundings and is shocked not just to come across a leveret on the path, but to find herself trying to save its life, taking it into her cottage and learning how to care for it while trying not to destroy its essential nature by turning it into a domestic pet. Researching all that there is to know about hares, and what they symbolise in the social and cultural geographies of the countryside in England and elsewhere, Chloe is drawn into and tells a whole story of the world of this exceptional and now increasingly rare animal.

Young Hare

Since no one could reassure Chloe that it was possible to raise a leveret and warned her that the most likely result of her efforts would be disappointment, and sadness, she is surprised by the outcome of her everyday devotions, which is the survival of the hare. Chloe refuses to name the leveret lest she become too close to it, and simply calls it hare, reminding herself repeatedly of her intention, which is to return the leveret to the wild. The book tells of Chloe’s gradual relationship with the leveret, finding out about the nature of the hare as a unique kind of animal, what it eats and how it lives, the fragile conditions of its habitat and the growing threats to the ecology that supports its flourishing. Slowly, but surely, despite her attempts to remain rational in her enquiry, Chloe is completely undone by the tender bond she cultivates with the leveret as it grows and thrives and teaches her all that she needs to know about herself and the way she is living her own life.

As it did for Richard Shimell, the art of close observation to nature enables Chloe to pay finer attention to her own existence and to come to understand a growing sense of unease that all is not well in her own life. Gradually, she begins to realise that she has been lacking a basic alignment with what living closer to nature has allowed her to understand: the healing potential of simple, predictable routines; time and space to be and to breathe; to stop and take care and sleep well; to work out how to exist alongside another being in a relationship of mutual care and companionship as an act of devotion. Slowly, by letting go of the tension and anxiety associated with the breakneck speed of her former way of being in the world, Chloe discovers a new sense of balance as an antidote to the addictive self-abandonment she believed was required for what counts as success in modern life.

“Living side by side with the leveret changed me in unexpected ways. Before it came into my life, I had put work ahead of almost every commitment. I realised now that I had toughened myself up to cope with a demanding work environment, adopting a persona and way of working that was in some respects exhausting and alien to me. Beneath the carapace was a temperament that longed for quieter, more gentle rhythms. Whereas I had been impervious to warnings about burnout from friends, the leveret worked on my character soundlessly and wordlessly, easing some of the nervous tension and impatience that I had been living with as a result of a life constantly on the move and on call for others.”

“Since that first day when I found her, it has felt as if a spell was cast over this corner of the Earth and me within it. I have stepped out of my usual life and had the privilege of an experience out of the ordinary. Had it not been for the hare, my life would have continued along its familiar grooves. I may never have questioned my habits or career and missed out on so much as a result.”

“The hare has taught me patience. She showed me a different life, and the richness of it. She made me perceive animals in a new light, in relation to her and to each other. I have learned to savour beautiful experiences while they last – however small and domestic they may be in scope. The sense of wonder she ignited in me continues to burn, showing me that aspects of my life I thought were set in stone are in fact as malleable and may be shaped or reshaped. She did not change, I did. I have not tamed the hare, but in many ways the hare has stilled me.”

Chloe’s meditation on what it means to take care of a leveret offers a powerful contemplation to us all about what it means to take care of a life. This has certainly always been a theme of enquiry for us on yoga retreat. Many guests, at the height of successful and exciting careers, (and this was certainly always also true for me as a busy academic with senior leadership responsibilities at university), join yoga retreats, and perhaps enjoy them regularly, as an effective way to recalibrate, to rest and come back into alignment in beautiful environments that allow for quietening, stillness and a chance to recuperate, so that life and work can go on.

Many guests on winter retreat in January have joined me in previous years on summer retreat in the southeastern province of Sardinia. This is one of the five places on the planet – the Blue Zones - where people are living the longest healthiest happiest lives, simply because in these locations, the same nine variables come together to create the conditions for human flourishing. In these places of the world - Ogliastra in Sardinia; Ikaria in Greece; Nicoya in Costa Rica; Okinawa in Japan and Loma Linda in California – people eat good food grown in good soil; enjoy meaningful work not necessarily well paid; enjoy friendship, family and community on a regular basis; drink a glass of locally produced wine with food once a day in good company, and often experience a sense of awe and wonder in the face of being in the world, because of the beautiful natural environments they inhabit.

Sardinia: mountain spa

Sardinia: medicinal waters

People in these places where centenarians are numerous and celebrated, do not practice yoga, but they do take part regularly in activities that allow the joints and muscles of the body to be mobilised and strengthened through natural movement such as gardening, fishing, walking, dancing, swimming and manual labour. Perhaps most important of all, they avoid stress and prioritise rest with a high cultural value placed on ‘downtime’ – or afternoon siesta. They do not work too hard, which means there is no expectation of it being normal to push the body and mind beyond healthy limits. I have reflected with guests on summer retreat every year for the last five years about this concept of downtime, eventually becoming aware myself that I had sustained an unconscious certainty that as long as I swam, took long walks and practised yoga and meditation regularly, I could work as hard as I needed, for as many years as required, to sustain and progress my career, support my family financially, be at the centre of a busy family life, and commute between cities for work whilst also making it all appear to be effortless.

What strikes me about Raising Hare, is the opportunity for reflection and life change that Covid isolation made possible for so many people. The interruption to the usual ordering of reality and ways of working and living was useful and important. It reminds me in many ways of what it means, as a yoga teacher, to offer a retreat, to invite guests to share in an enquiry about the value of purposefully stepping out of familiar ways of life for a moment, to take a pause for a few days or weeks every year and seek sanctuary whilst experimenting with living differently and being curious about change.

For me, this means finding a beautiful place in nature to host a retreat where it is safe to rest and reflect; to move and breathe and take nourishment in ways that bring body and mind back into alignment; to restore a sense of the goodness of life; to feel gradually more energised and at ease, to restore sleep and digestion, to find a sense of balance and courage in heartwarming company to touch on uncomfortable truths; to navigate expected or unexpected life challenges; to question unconscious habits of existence and to find hope for the future, especially when the state of the world is frightening and increasingly uncertain. This is what makes yoga a warrior’s practice – it prepares us to stand in the truth of what needs to be known - and works on the assumption that truth arises from learning how to pay attention, to listen again and again, with increasing sensitivity, to the wisdom of the body. This requires a constant vigilance about the ways in which the mind overrides the signals of the body, so that what is familiar, habitual and culturally expected, is not challenged and the status quo is preserved.

Learning to listen to the body, in the same way that we learn how to observe the beauty of the environment, brings about a process of re-wilding our own lives, so that we might come into alignment with nature, so that we might know and feel more readily when we are out of balance not just personally, but also culturally, socially and economically, which always means that practising and teaching yoga and writing about nature is inevitably also a political act.

Winter in Norfolk: frost at dawn

Resting in the beautiful surroundings of West Lexham, in Norfolk, guests on winter retreat had the lovely experience of seeing hares for themselves on their walks on the land, and a few people felt the quiet excitement of close-up sightings of the small wild deer in this area. Each day we spent the morning in quiet contemplation, moving through energising and strengthening sun salutations inspired by alignment-based hatha yoga, and Qi Gong. We enjoyed phenomenal vegetarian food prepared by our retreat chef for the weekend, Lucy Cheney, and exquisitely sensitive reflexology treatments from herbalist and essential oils expert, Rieko Oshima-Barclay.

In the afternoons, we enjoyed downtime by the fire, silent walks on the quiet lanes winding their way through the winter landscape, and we took our time to take it easy, to rest and find laughter and solace in new acquaintances and conversations with old friends. It was remarkable this year to discover that so many of us were making sense of profound life change of one kind or another. Sadly, some guests were grieving for loved ones lost in 2024, wondering with such tenderness alongside beloved family members on retreat, how to make sense of the year ahead; others, including me, were committed to significant life change in 2025 and exploring new career paths. Some people were preparing for retirement at the end of long and esteemed careers and together, we were all feeling uncertain at the beginning of the year about how the future might unfold. Alongside one another, we found a stable ground in the daily practice, came down to earth to breathe and lend support to feelings of uncertainty, and to stabilise before initiating any action for the coming year. The metaphors of the movement practice served us well and settled our nerves. The special value was not lost on us of a winter retreat in the first weekend of the year, after the excesses of the festive season and, for some, the often upsetting social and emotional demands of Christmas no matter how well designed and organised. We all needed some timely medicine for the heart and soul and to breathe under open skies again.

Norfolk in Winter: expansive skies above Holkham Beach …

The final book in the winter story pot that I did not declare at the time of our retreat, but want to reflect on here, was left in my pigeonhole at work, in a busy academic department of Social Anthropology, mid-semester, around the end of October. I spied a single book, a paperback, and noticed it had a beautiful postcard note inside saying, simply: “I just finished this and thought you might enjoy it.” The book was one in a series of gifts from a colleague, friend and fellow yogi who joined us on retreat; she has a knack for giving me books that somehow resonate exactly in that moment of time, with my state of being, or state of enquiry in life, or more specifically my current practice of enquiry in yoga. This time, the resonance of the book was uncanny.

My colleague and I had only recently had a cup of tea and a chance to catch up after a long time not having run into each other in the department and after a busy summer of travelling for each of us in different parts of the world. I remember thinking how frustrating that time together was, and how sad I had felt as I left the encounter, feeling that I hadn’t been able to be honest about what was moving powerfully through my life. I sensed a loss of intimacy arising from a lack in me on this occasion of authenticity and truthfulness. We had exchanged notes on our lives and work and our personal lives in some detail, but I hadn’t yet been ready, or brave enough, to declare the imperative that was taking shape in me to undertake an urgent and radical revolution in my life.

It hadn’t been quite the right moment to reveal that I was seriously contemplating early retirement from academia to make space and time for a new career and a very different way of life. My interest in the human condition is constant, I can’t help but attend to that as an aspect of who I am, and what fascinates me about being in the world, but I have been determined for a while now to find a new approach to the questions I am interested in, not just as a social anthropologist with an interest in all things urban and how to live well in the city; not just as a yoga teacher, but also as a psychotherapist now with a special interest in embodiment.

I was excited about how these three strings to my bow were going to come together to make possible a new of application of my analytical curiosity and concern for humanity, and the world, but I didn’t yet have the words to articulate my determination when I was swapping notes with my friend and colleague at the beginning of the winter season.

Bizarrely, the gift of the book in my pigeonhole just a week later, after our cup of tea, was a beautiful autobiographical account by Katherine May entitled Wintering: the power of rest and retreat in difficult times. Like Raising Hare this book also tells the story of a life thrown into disarray by an enforced period of relative stillness and quiet simplicity – a coming to a standstill and state of rest – that the author equates with what winter brings to the natural world: a fallow period, a slowing down and stripping back necessary to the cycle of nature, but also the comfort and care required to hibernate well and survive the hardships of winter.

Hibernating well …

Like Chloe Dalton, and Richard Shimell, Katherine May, an academic in a state of significant life change, finds in the observation and investigation of nature, not just consolation and healing, but also a metaphor in winter for the difficult process of profound transformation that is required to bring the world to a stop for a while. It is the change of pace in the cyclical nature of the seasons, and the interruption of the usual routines of business-as-usual that allowed Katherine time and space not just for rest and restoration, but also for self-reflection, for feeling difficult sometimes unbearable emotions, and weathering the darkness.

“Plants and animals don’t fight the winter; they don’t pretend it’s not happening and attempt to carry on living the same lives that they lived in the summer. They prepare. They adapt. They perform extraordinary acts of metamorphosis to get them through. Winter is a time of withdrawing from the world, maximising scant resources, carrying out acts of brutal efficiency and vanishing from sight; but that’s where the transformation occurs. Winter is not the death of the life cycle, but it’s crucible.”

“Doing these deeply unfashionable things – slowing down, getting enough sleep, resting – is a radical act now, but it is essential. This is a crossroads we all know, a moment when you need to shed a skin. If you do, you’ll expose all those painful nerve endings and feel so raw that you’ll need to take care of yourself for a while. If you don’t then that skin will harden around you.”

On our last night of the weekend in Norfolk, in the dark and under the rain, we committed to the flames of the fire pit at night, the gorgeous Wild Cards from the Lost Words and Spell Songs series on which we had earlier written down what we wanted to leave behind in 2024. And we took away with us, or buried in the earth at West Lexham, the cards on which we had declared, bravely, what we wanted to grow and bring into our lives in 2025. I wonder now, as I write, at the end of February, almost eight weeks later, what is taking root in us all and beginning to blossom, as the first signs of spring show themselves as snow drops in the ground.

Snowdrops in the woods …